| |

2010s |

| |

The Art of Fielding, Chad Harbach

Beautiful Ruins, Jess Walter

Dead Stars, Bruce Wagner

Dept. of Speculation, Jenny Offill

The Devil All the Time, Donald Ray Pollock

Freedom, Jonathan Franzen

The Goldfinch, Donna Tartt

Hallucinations, Oliver Sacks

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, Rebecca Skloot

The Imperfectionists, Tom Rachman

The Interestings, Meg Wolitzer

The Maid’s Version, Daniel Woodrell

Mortality, Christopher Hitchens

The Sense of an Ending, Julian Barnes

The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History, Elizabeth Kolbert

The Snow Queen, Michael Cunningham

A Visit from the Goon Squad, Jennifer Egan

We Are Not Ourselves, Matthew Thomas

We the Animals, Justin Torres

What You See in the Dark, Manuel Muñoz

The Woman Upstairs, Claire Messud |

|

|

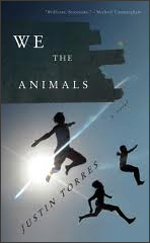

We the Animals, Justin Torres

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, August 30, 2011

It’s odd, really. It happens ridiculously quick, we all know this by now, but somehow the speed at which life passes still manages to stir surprise. Stranger still is how so many of the moments manage to hang, suspended in time, while simultaneously burning holes straight through the dissolve of yesterdays.

Lina stood there for a while, then reached into her smock and pulled out a tissue, taking our mother’s face in her hands and wiping it down, tucking wisps of hair behind Ma’s ears. We were kneeling on the floor, not two feet away from them, and the longer Lina stood there, grooming Ma, the less we paid attention to the groceries. Then Lina started kissing Ma all over, little soft kisses, covering Ma’s whole face with them, even her nose and eyebrows. Then she put her lips on Ma’s lips and held them there, soft and still, and nobody—not me, not Ma, not Joel or Manny, nobody—said a word. There wasn’t a word to say.

With each hiccup of joy, sorrow, and ennui, life cascades in flashes of moments that either possess the depth of power to register as lasting memories—signed, sealed, delivered, into the future—or else lack the strength to hold on, moments washed away in the tsunami of seconds rushing by as if they never happened at all. Except that they did.

We didn’t have anywhere to go in particular, so we just drove, cutting through the night, smooth as nothing. We drove through the neighborhood, then out of it, down back roads, past cornfields, Ma in the front, nestled up close to Paps, her head on his shoulder, the wind tossing her hair around both of them, and us boys bumping along in the back, aiming our guns up at the stars above and shooting them down, one by one.

You cannot remember the beginning before the memories managed to stick. Maybe nobody is truly present when they come into the world, at least not as the individuals they will one day become. Identity remains tucked away within an embryo, refusing to open until years after that precious first breath of life finds you alive in the “we” of a family unit: mother, father, siblings. Your movements and thoughts meld into a collective that interacts with its surroundings as one.

After a while Manny started up again, talking to himself, plotting, saying, “What we gotta do is, we gotta figure out a way to reverse gravity, so that we all fall upward, through the clouds and sky, all the way to heaven,” and as he said the words, the picture formed in my mind: my brothers and me, flailing our arms, rising, the world telescoping away, falling up past the stars, through space and blackness, floating upward, until we were safe as seed wrapped up in the fist of God.

At last, it begins, bursting light into days previously filled with a darkness reserved for black holes. You can see it now: a memory built to last. Maybe it is even beautiful, like she was beautiful, like you all were beautiful. You don’t know why exactly that this one managed to navigate into view, but now that it has, you follow its path from present to past, arriving at an outline and then to its core, a fully developed snapshot glued to a page in the family album of your mind.

A brass-handled mirror lay on the bureau, and as soon as Ma raised it to her face, tears came and sat on her eyelids, waiting to fall. Ma could hold tears on her eyelids longer than anyone; some days she walked around like that for hours, holding them there, not letting them drop. On those days she would trace her finger over the shapes of things or hold the telephone on her lap, silent, and you had to call her name three times before she’d give you her eyes.

And then it happens. For some, it is well-defined, neatly trimmed in an otherwise random moment that pulls apart forever the me from the we. It is when they arrive, right about the time when nothing can ever be the same again.

THEY WERE GATHERED in the front room, and the air reeked of grief. The force of their eight eyes pushed me backward toward the door; never had I been looked at with such ferocity. Everything easy between me and my brothers and my mother and my father was lost.

The awakening is nothing if not bittersweet, when the fire of childhood is put out and a flicker of knowledge is replaced with a vivid awareness of things both scary and profound.

“What happens when you die?” I asked. “Nothing happens,” he said. “Nothing happens forever.”

We remember when we were carefree, when we were children, when we played and fought like a pack of wild beasts, back when the future didn’t exist any more than the past. When we were together. We remember.

You remember.

-G

|

|

|