| |

2010s |

| |

The Art of Fielding, Chad Harbach

Beautiful Ruins, Jess Walter

Dead Stars, Bruce Wagner

Dept. of Speculation, Jenny Offill

The Devil All the Time, Donald Ray Pollock

Freedom, Jonathan Franzen

The Goldfinch, Donna Tartt

Hallucinations, Oliver Sacks

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, Rebecca Skloot

The Imperfectionists, Tom Rachman

The Interestings, Meg Wolitzer

The Maid’s Version, Daniel Woodrell

Mortality, Christopher Hitchens

The Sense of an Ending, Julian Barnes

The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History, Elizabeth Kolbert

The Snow Queen, Michael Cunningham

A Visit from the Goon Squad, Jennifer Egan

We Are Not Ourselves, Matthew Thomas

We the Animals, Justin Torres

What You See in the Dark, Manuel Muñoz

The Woman Upstairs, Claire Messud |

|

|

The Goldfinch, Donna Tartt

Little, Brown and Company, October 22, 2013

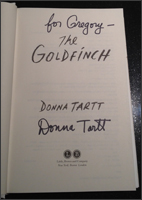

Look, but please do not touch. It is a first edition. My very own signed copy of The Goldfinch. You will have to excuse me but I want it preserved in pristine, mint condition. It is why I also bought the Kindle edition, so as not to mess with my precious hardcover as I read along.

“Idolatry! Caring too much for objects can destroy you. Only—if you care for a thing enough, it takes on a life of its own, doesn’t it? And isn’t the whole point of things—beautiful things—that they connect you to some larger beauty? Those first images that crack your heart wide open and you spend the rest of your life chasing, or trying to recapture, in one way or another?”

As riveting as her novels, so too are her conversations, decade-in-wait appearances coinciding with her latest release. At an event sponsored by the Chicago Humanities Festival, I am two rows back as Donna Tartt speaks about her novel, her writing process, her childhood passion for reading, her attachment to characters like Peter Pan and Oliver Twist, her love for the writings of Robert Louis Stevenson, and so much more. She is predictably well-dressed in a getup as handsomely constructed as one of her sentences, here sporting a trademark suit that on this night is paired with very cool Alice in Wonderland black and white striped socks. Her perfectly coiffed black bob seems to possess a life of its own as she leans forwards and backwards in her chair while she explains that there are generally two things that we think of as priceless in this world: of course, life itself, but also art, the great works that are irreplaceable originals. The immortal objects that pass through centuries of imaginations and hearts, scorching souls across the limitless expanse of history.

“Great paintings—people flock to see them, they draw crowds, they’re reproduced endlessly on coffee mugs and mouse pads and anything-you-like. And, I count myself in the following, you can have a lifetime of perfectly sincere museum-going where you traipse around enjoying everything and then go out and have some lunch. But—” crossing back to the table to sit again “—if a painting really works down in your heart and changes the way you see, and think, and feel, you don’t think, ‘oh, I love this picture because it’s universal.’ ‘I love this painting because it speaks to all mankind.’ That’s not the reason anyone loves a piece of art. It’s a secret whisper from an alleyway. Psst, you. Hey kid. Yes you.”

Here I am, at long last reading the third novel by my favorite living writer. On so many pages it happens all over again. I hear a whisper from the alleyway directed at me, me, me.

“An individual heart-shock. Your dream, Welty’s dream, Vermeer’s dream. You see one painting, I see another, the art book puts it at another remove still, the lady buying the greeting card at the museum gift shop sees something else entire, and that’s not even to mention the people separated from us by time—four hundred years before us, four hundred years after we’re gone—it’ll never strike anybody the same way and the great majority of people it’ll never strike in any deep way at all but—a really great painting is fluid enough to work its way into the mind and heart through all kinds of different angles, in ways that are unique and very particular. Yours, yours. I was painted for you.”

A paragraph feels ripped from my subconscious. Another is just too beautiful or heart-wrenching to not give rise to the things that stir the soul. The pages turn and connections take root, intensifying, solidifying. As example, in The Goldfinch, at times I feel outed in my sometimes far too grim way of thinking about the meaning of life or lack thereof and what waits for us all in each of our lonely decay.

Soon, I knew, the night sky would turn dark blue; the first tender, chilly gleam of April daylight would steal into the room. Garbage trucks would roar and grumble down the street; spring songbirds would start singing in the park; alarm clocks would be going off in bedrooms all over the city. Guys hanging off the backs of trucks would toss fat whacking bundles of the Times and the Daily News to the sidewalks outside the newsstand. Mothers and dads all over the city would be shuffling around wild-haired in underwear and bathrobes, putting on the coffee, plugging in the toaster, waking their kids up for school.

And what would I do? Part of me was immobile, stunned with despair, like those rats that lose hope in laboratory experiments and lie down in the maze to starve.

I was only a few hundred pages into The Goldfinch but knew it was surely the lone reason for my melancholy. I know it because it was a weekend, a window of reprieve typically reserved for contentedness at a minimum, euphoria at a maximum, but this one was mired inside sadness. It was the book doing its thing, wielding its magic, weaving its spell.

There was no end in sight to the present horror, plenty of external, empirical horror to line up with my own endogenous supply; and, given enough dope (inspecting the bag: less than half left), I would happily have set up a fat line and toppled right over: great-souled darkness, explosion of stars.

I see the crowds, lines of people clutching their satchels that are each carrying a copy of the book. They come in droves all over the world, flocking to see Donna Tartt in person. But it’s funny how the universal appeal—craze—does nothing to expand the confines of the conversation. It is two and only two, author/reader. It is silent, a kind of telepathy. In a place of make-believe, a writer and reader become entwined.

Why did I obsess over people like this? Was it normal to fixate on strangers in this particular vivid, fevered way? I didn’t think so. It was impossible to imagine some random passer-by on the street forming quite such an interest in me. And yet it was the main reason I’d gone in those houses with Tom: I was fascinated by strangers, wanted to know what food they ate and what dishes they ate it from, what movies they watched and what music they listened to, wanted to look under their beds and in their secret drawers and night tables and inside the pockets of their coats. Often I saw interesting-looking people on the street and thought about them restlessly for days, imagining their lives, making up stories about them on the subway or the crosstown bus.

In speaking of my own personal connection with Tartt, I enjoy her novels as great stories that make me want to read on to find out what happens next, but with each novel, I cannot help but also feel like I am learning more and more about Tartt herself. Sometimes too, myself. I draw a parallel to what Tartt says and writes about the magical duality of a great painting: how you can see its illusion but also if you get close enough you can see the painter’s brushstrokes, the painter’s hand. I feel that same sense of duality when I read a Donna Tartt novel seeing Tartt’s own brushstrokes and I begin to peer closer into her own mind, her own thoughts overlaid on the motives, fears, joys, and more of Theo, Henry, Harriet, or any of her other many memorable characters. In the previous excerpt, I wonder if Tartt is revealing more than a bit about herself, perhaps admitting to her own obsessions as writer and her own need to inhabit and create lives that are composites of those she herself has come across. I wonder about Tartt’s own experiences in Amsterdam, Las Vegas, and New York, and contemplate how these experiences shaped Theo’s epic journey. All the while, as reader and fan, I inch closer to an artist I admire deeply.

“Rembrandt. Velázquez. Late Titian. They make jokes. They amuse themselves. They build up the illusion, the trick—but, step closer? it falls apart into brushstrokes. Abstract, unearthly. A different and much deeper sort of beauty altogether. The thing and yet not the thing. I should say that that one tiny painting puts Fabritius in the rank of the greatest painters who ever lived. And with The Goldfinch? He performs his miracle in such a bijou space. Although I admit, I was surprised—” turning to look at me—“when I held it in my hands the first time? The weight of it?”

Coming full circle, I hold the novel The Goldfinch in my hand. I could tell you, my imaginary reader, what I have told close friends and family: how this book contains themes that have the power to change a life. A bleak, what’s-it-all-mean-but-nothing-in-the-end outlook feels downright challenged by Tartt in a wonderful and powerfully life-affirming way. But what I would rather leave you with is this, a picture of my very own signed first edition.

The dried ink on the title page secures the memory of a special night What is more, I now possess a priceless addition to my own personal library. Not priceless in comparison to a Rembrandt or Carel Fabritius painting, and certainly not even the only copy of the novel in print. Far from it. Nevertheless, it is the one and only copy that was signed for me and me alone, and for that, I do not apologize or mince words when I say that this particular copy of this particularly wonderful book is very much priceless indeed.

One thing I know to be true in this life: time sure does fly. Conversely, something tells me the next ten or so years will not pass soon enough. Let’s just say a little birdie told me so.

-G

|

|

|