| Music | Literature | Film | Index | About |

|

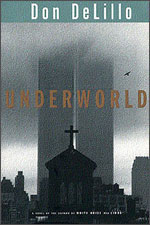

Underworld, Don DeLillo Scribner, October 3, 1997

The term epic can be a bit overused. But is there any other way to describe a novel that covers nothing less than half a century and weaves fictional and non-fictional worlds together in such a way that ultimately unifies the dense mass of exploding debris to ultimately leave you awestruck? With apologies in advance to Andy Warhol and the Velvets, but within the mass of the exploding plastic inevitable, we begin to understand that the national archives are littered and chalk full with more than mere objects. Whereas the initial focus here is on a baseball that is symbolic of a beloved national pastime, the search for said baseball leads us on a journey with a far more expansive reach. DeLillo is interested in collecting all of it, knowing that a more complete set is essential in examining the collective state of mind and growing paranoia of a changing nation. As the second half of the twenty-first century comes more sharply into focus, so too does our understanding of our place within it, as well as all that we did individually and collectively to find ourselves here. When you finally put Underworld to rest, you exhale, reflecting not only on only DeLillo’s ambitious achievement, but also the emotions it incites along the way. Moreover, I think it would be difficult for any fan of literature to read this novel and not, as a result, begin to whisk a world full of foamy, oozing adjectives to attach to the virtuoso writing style of Don DeLillo. There’s a man in the upper deck leafing through a copy of the current issue of Life. There’s a man on 12th Street in Brooklyn who has attached a tape machine to his radio so he can record the voice of Russ Hodges broadcasting the game. The man doesn’t know why he’s doing this. It is just an impulse, a fancy, it is like hearing the game twice, it is like being young and being old, and this will turn out to be the only known recording of Russ’ famous account of the final moments of the game. The game and its extensions. The woman cooking cabbage. The man who wishes he could be done with drink. They are the game’s remoter soul. Connected by the pulsing voice on the radio, joined to the word-of-mouth that passes the score along the street to the fans who call the special phone number and the crowd at the ballpark that becomes the picture on television, people the size of minute rice, and the game as rumor and conjecture and inner history. There’s a sixteen year old in the Bronx who takes his radio up to the roof of his building so he can listen alone, a Dodger fan slouched in the gloaming, and he hears the account of the misplayed bunt and the fly ball that scores the tying run and he looks out over the rooftops, the tar beaches with their clotheslines and pigeon coops and splatted condoms. The game doesn’t change the way you sleep or wash your face or chew your food. It changes nothing but your life. That’s it. Perhaps it is a cop-out to start and stop there, avoiding any real dissection of the novel. But in recognition of the sparse introduction that ultimately led me here, I think stopping is appropriate. That’s it. Go ahead, take a swing and just see where it takes you. -G

|

|

||||||