| Music | Literature | Film | Index | About |

|

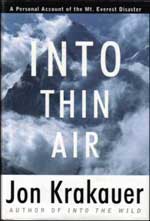

Into Thin Air: A Personal Account of the Mt. Everest Disaster, Jon Krakauer Villard Books, April 22, 1997

It was as if there were an unspoken agreement on the mountain to pretend that these desiccated remains weren’t real—as if none of us dared to acknowledge what was at stake here. Injury from falling seracs. Frostbite. Dehydration. Exhaustion. Muscle fatigue. Mental impairment. Shortness of breath. Destroyed brain cells. Thickened blood. Rapid heart rate, leading to heart attack. Plunging to death in a crevasse. Shock. Hypothermia. Hypoxia. Hemorrhaging. High-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE). High-altitude cerebral edema (HACE). The preceding lists a random sampling of the challenges imposed on the body at extreme altitudes. A shot of dexamethasone might revive the gravely ill, but enduring the intense physical demands of an ascent requires more than a desperate injection. Success takes a peculiar mind-set, functioning outside the realm of what is feasible, comfortable or remotely rational. Unfortunately, the sort of individual who is programmed to ignore personal distress and keep pushing for the top is frequently programmed to disregard signs of grave and imminent danger as well. This forms the nub of a dilemma that every Everest climber eventually comes up against: in order to succeed you must be exceedingly driven, but if you’re too driven you’re likely to die. On May 10, 1996, nine people, including experienced guides, lost their lives on the roof of the world, as a raging storm unexpectedly attacked climbers at various stages on Everest’s tip, a mystic jut of real estate, whose majestic sight has attracted transcendentalists from continents across the globe for over a century. The ink-black wedge of the summit pyramid stood out in stark relief, towering over the surrounding ridges. Thrust high into the jet stream, the mountain ripped a visible gash in the 120-knot hurricane, sending forth a plume of ice crystals that trailed to the east like a long silk scarf. That some escape alive speaks of miracles. Stomaching a survivor’s intimate account of the personalities and factors contributing to the 1996 disaster tries one’s nerves and powerfully functions as serious reflection of personal limitations. Regardless, there exist those who finish the testament convinced that a bid to summit Everest remains a facile goal. Everest has always been a magnet for kooks, publicity seekers, hopeless romantics, and others with a shaky hold on reality. Reaching for the sky assumes noble consideration, but even those who spend years training for the feat are not immune to the unpredictability of meteorological strength, which has exercised up and down the mountain, since creation. When presented with a chance to reach the planet’s highest summit, history shows, people are surprisingly quick to abandon good judgment. Nature, for the record again and again, retains the upper hand in battles against man. The narrative also conversely rescues a number of dreamers, who acclimate to an acceptance of limitations more astutely than the person clipped into a pair of crampons at Base Camp, and the lesson for those abandoning castles in the air is not a lament of disappointment or regret. Nor does deterrent halt individuals from striving to explore rough terrain altogether. Rather, a vicarious journey cultivates the framework to access our place in the world with a superior appreciation for things larger than self-centered motives. Leaving a footprint on alpine ranges, along with less literal elevated ambitions, can protrude somewhat out-of-sight, but grandeur, like so much, is loftily admired from afar, in relative quiet save the squalls ordained to harmoniously scale mythical scope. -MEG

|

|

||||||