| Music | Literature | Film | Index | About |

|

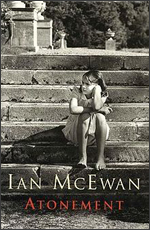

Atonement, Ian McEwan Jonathan Cape, January 1, 2001

It was the summer of dark secrets. The summer of unrequited love. The summer gone out of bounds. You were 19. Not fully a man but fused with the gush-charge that shoots wildly through the flesh of young men. You were not innocent. Not ignorant. Just terribly dangerous. Hugely careless. Out of control. Iniquitous. Reckless and oh so cowardly. You were a hot summer brushfire destroying everything and everyone within its path. But who could stop you? It was the summer of cold emerald lakes and golden Sierra sun. Slick-wooden docks and snowcapped mountains. Waterskiing and swimming and playing basketball. It was the summer of sweet Ponderosa pine and clean forest air. The piercing of bare feet against conifer needles sticking out prickly from cool sand. It was the summer of smoked mackerel and clean college summer camp. Of frozen bodies with blue-bloated faces fished out of icy waters with no one knowing why or how they got there. The leaves became nutty brown, the branches glimpsed among the foliage oily black, and the desiccated grasses took on the colours of the sky. It was the summer of jackpots and nickel slots clanging wildly out of brightly lit casino machines. Beer and Snakebites and crisp corn dogs. Soft sandwiches and drifting nowhere out on a crystal lake on a powder-white boat. It was the summer of Stephen King novels and Raiders of the Lost Ark. The song “Into the Night” wafting softly from a shiny speed boat radio. Crisp, starry nights. Dark nights. And everything bad that happens in the night. And crossing the border of that which is good or bad. Wrong or right. Destroying a friendship forever. It should have ended there, this seamless day that had wrapped itself around a summer’s night. Atonement is a masterpiece. The perfect novel. It ranks among Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse to which the narrator openly pays homage. The prose is exquisitely crafted. Poetic. It casts the reader deep inside the minds and hearts of each individual character. You become each character. You understand their thoughts. Their fears and desires. Their loves and losses. And ultimately, you are deceived and confessed to by the characters themselves. You are shown—correct that, you feel along with them—the immitigable misery and excruciating beauty and utter joy that makes up this that is life. Chiefly, the shear, unadulterated and hugely inexhaustible power of love. I’m too old, too frightened, too much in love with the shred of life I have remaining. It would be sweet to think so. That love is all-powerful. That love is eternal. Immovable. That love is stronger than even hate or death or war. That you yourself might one day be forgiven for your sins. The crimes of your past. That the damage that you’ve done might one day be absolved. Atoned. If only one were religious enough that this might happen. But if one isn’t religious then there is no hope whatsoever. Other than to live with the iniquity and suffer in silence. Pay for the misbegotten deed. To live, but to know way down in your heart of that knowing. And never to forget or forgive yourself. Or one day, perhaps write it all down on a page with the hope that the crime will be forgiven by posterity. Not forgotten. Just forgiven. But then who deserves to be forgiven? “If I fell in the river, would you save me?’’ It is winter and you are drunk and alone sitting at the edge of an icy wooden dock. The wet snow is pelting against your face and the water is dark and choppy. There is a deep silence across the lake, a silence you do not understand, and you are crying. What for? A love and action that does not speak its name? So you sit. Too young to realize how stupid you or your self-pity are. An hour later you will be driving home onto a freeway entrance on the wrong side of the road more drunk than before. But for now you sit in judgement before the silence of the lake. The leaves have long since fallen. You can either slip right here, by accident, and drown into the blackness of the water, or die later on in a head-on car collision. You decide. But neither happens. Instead you leave one day and move far away never to come back again. You will continue to live. Yes. As do all the good and the bad, the hurtful and the pleasant, all the ebb and the flow, the wax and the wane of the memories and moments and regrets that live like sorry ghosts deep within you.

|

|

||||||