| Music | Literature | Film | Index | About |

|

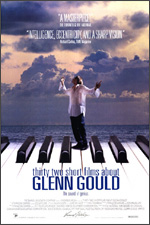

Thirty Two Short Films About Glenn Gould, Directed by François Girard Max Films, September 14, 1993 (Canada) Screenplay: François Girard, Don McKellar, including the writing of Glenn Gould Starring: Colm Feore, Derek Keurvorst, Katya Ladan, Devon Anderson, Joshua Greenblatt, Sean Ryan, Kate Hennig, Sean Doyle, Sharon Bernbaum, and David Hughes

Looking to the sky, there are times you wish you could reach up and touch the clouds or lay down in their soft white billowy embrace. When beauty inspires us we search for ways to get closer. For François Girard, in relation to his admiration of Glenn Gould, a desire to get closer to the subject in order to pay proper tribute presented the director with a particularly daunting task: How could Girard capture the essence of true genius? Refusing to settle for a two-dimensional biopic that would ultimately only piece together a flimsy overview of the man, Girard opted to forego the typical Hollywood template. Gould deserved more than that. He was one-of-a-kind. Girard searched for something more. Ultimately, he found it by employing a narrative structure that mirrored Gould’s famous Goldberg Variations. The unique result—thirty two variations of a man—is a film that I believe touches the clouds. Gould: l could read music before l could read words. I heard of Glenn Gould through a friend. My head had been buried in a cool rock and roll sands among Crickets and Beatles and Stones held my gaze. I was electrified by Neil Young. I melted in the harmonies of The Everly Brothers. I explored The Doors of perception. I woke up from it all in a punk frenzy and raged against the machine. Alive in the ’90s, I felt the excitement of fuzz emanating inside the garage. Gould: l often think how fortunate l was to have been brought up in an environment where music was always present. Who knows what would have become of me otherwise? The progression of this fan’s journey was paved with wildly inspiring performances, both live and between the grooves. But I wasn’t naive. Was I experienced? (Have you ever been experienced?) I knew there was much more out there in the many roads and the detours not taken. I’d tiptoed gingerly into jazz—Coltrane, Monk, and Miles—almost fearful of the financial implications of where such meandering might lead. (Record store bins. Downloading frenzies. Who had the money or time?) I had only scratched the surface of country music—real country music—and I knew I was well behind that curve too. And then came a tip from a friend to check out the world of Glenn Gould. He suggested I go see the film about him with the strange title. Sure … why not? The marriage of varying art forms (in this case, music and film) had excited me many times before, from A Hard Days Night to Gimme Shelter, from The Wall to Amadeus and countless others still. In the case of Thirty Two Short Films about Glenn Gould, I’m just not sure I was prepared for the resulting awakening. I had thought of classical music much like poetry: something foreign and beyond my grasp. And yet, I found the film so exciting on so many different levels, that I had no choice but to explore the music and ideas of Glenn Gould further. Gould: The artist should be granted anonymity. He should be permitted to operate in secret as it were, unconcerned with or better still unaware of the marketplace’s demands, which demands given enough indifference on the part of enough artists … will simply disappear. Given that disappearance the artist will then abandon his false sense, of public responsibility, and his audience or “public” will relinquish its role of servile dependency. And never the twain shall meet. I’ve been to many greatest hits concerts in my time: Large venue shows with ridiculous ticket prices that feature the dreadful droll of fans singing karaoke along to their favorite tunes. When they weren’t singing, these same fans would bark out requests—Freebird!—in hopes that the trained monkeys on stage would obey. If you have ever experienced the opposite end of the spectrum—the communal euphoria of audience and performer becoming one, lost in another dimension where the artist really is invisible (as Gould longed to be), channeling something far greater than the sum of the parts (performer, audience, and music)—things can never be the same thereafter. From what I have read, Glenn Gould’s live performances were portals to another level of consciousness, celebrations of the delicate purity inherent in every last note that bled through him. That his performances could achieve such heights was the greatest tribute Gould could give back to the music itself, the music he loved so dearly. If this elevation could not be reached (since it required more than just the artist to reach it), then there was simply no point in performing at all. Doing so would cheat the music, the listener, and Gould himself. And so it made perfect sense that when Gould’s persona as resident genius became bigger than the magic and experience of the performance, it was simply time to move on. And so, just like that, there were no more live shows. It was time to focus his considerable energy into mastering the intricacies of the recording process. But why stop there? On to writing. He even went on to broadcast a radio show. Gould certainly utilized the time that he had in life with a level of awareness that so few possess. He understood just how precious and extraordinary every minute can be. I have a greater appreciation for classical music because of him, and I also have a greater understanding of how much of a contribution just one person can leave behind.

|

|

||||||