| |

2000s |

| |

After Dark, Haruki Murakami

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, Michael Chabon

Asterios Polyp, David Mazzucchelli

Atonement, Ian McEwan

August: Osage County, Tracy Letts

The Book of Revelation, Rupert Thomson

The Corrections, Jonathan Franzen

Chronicles Volume One, Bob Dylan

The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic and Madness at the Fair That Changed America, Erik Larson

Empire Falls, Richard Russo

A Fraction of the Whole, Steve Toltz

The Gum Thief, Douglas Coupland

A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, Dave Eggers

The Inheritance of Loss, Kiran Desai

The Inner Circle, T.C. Boyle

The Living, Pascale Kramer

Love in Infant Monkeys, Lydia Millet

The Monsters of Templeton, Lauren Groff

On Chesil Beach, Ian McEwan

Prodigal Summer, Barbara Kingsolver

The Secret Scripture, Sebastian Barry

The Story of Edgar Sawtelle, David Wroblewski

The Tender Bar, J.R. Moehringer

The Year of Magical Thinking, Joan Didion

Then We Came to the End, Joshua Ferris

Veronica, Mary Gaitskill

Zeitoun, Dave Eggers |

|

|

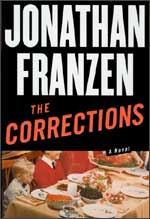

The Corrections, Jonathan Franzen

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, September 1, 2001

“Have no fear of perfection—you’ll never reach it.”

-Salvador Dali

Perfection exists. Cynics shield it from the faithful, insisting the world is an imperfect place. Everything is flawed. Nothing is perfect. But it lives and has been touched—clenched by acquisitive hands afraid to release and forever lose the joy of its company.

Book readers, for one, are trained to expect mere flourishes of genius in an author’s work. Witness the countless novels relegated to a single great sentence—a quote that rings notably true, witty or insightful—picked from a garden of wilting blooms. The selected phrase often ends up on a torn sheet of paper suspended by a magnet stuck to a refrigerator door or pinned to a cubicle wall. Regardless, focusing on a single line of text actually denotes a greater pronouncement about what might have been—the imperfect sentences failing to make the cut—than it exhibits a proclamation of enduring artistry.

Which explains why reading a paragraph of prose that flows elegantly from one sentence to the next is an elevated cause for celebration. A block of words on the page transformed into a meticulously arranged bouquet with no single bud drawing attention fetches greater value than the lone rose; each stem has a place in relation to the next, and the slightest rearrangement destroys the splendor. Such literary discoveries come accompanied by a requisite gasp of air, before eyes return to the indent where the words began. The paragraph is reread to confirm the impression’s authenticity. Proven real, pages are dog-eared for future reference, but the nagging issue of the surrounding inadequacy remains. Paragraphs before and after are cast away as immaterial. Perfection is reestablished sporadic, and one falls back into the trap of accepting complete transcendence as fiction.

Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections is fiction that transcends. The novel, a brick totaling nearly six hundred pages, sustains brilliance well beyond individual sentences or paragraphs. In particular, for nearly one hundred pages, an entire chapter, the writing is perfect.

The unnumbered third chapter titled “The More He Thought About It, the Angrier He Got,” which focuses on the life of Gary Lambert, a forty-three-year-old investment banker trying to establish a life for his family surpassing (i.e., correcting) the one he experienced as the oldest of three children born to Alfred and Enid Lambert in the fictional Midwestern town of St. Jude, is breathtaking because not a single word or thought is superficial. From Gary’s early musings about his deteriorating mental health to the pitch-perfect activities of a house run amok by his three young sons, his interactions with a suspiciously behaving wife to an interrupting call from Enid, urging one last family Christmas together, amid the household chaos, as well as discussions about video surveillance cameras, Franzen incorporates tension, realism, paranoia, heartbreak, theme, anger, humor, loss, psychology, and social commentary between every subject and verb on the pages. The feat is painful yet astonishing, and paragraphs build upon one another, resulting in unmatched rapture.

A quote is inadequate to convey the thrill. Excerpting a paragraph is about as useful as pulling a rose from a floral arrangement and expecting the recipient to appreciate the entire vase. Instead, enter the flourishing botanical gardens of The Corrections without assuming only one hundred pages of the book are worthy of a place on the refrigerator, if there were a magnet strong enough to hold them. The truth is every chapter is inextricably connected to the others.

Franzen places perfection within everyone’s grasp. What happens from that point onward is beyond his reach.

-MEG

|

|

|